Happy as a clam, is what my mother says for happy. I am happy as a clam: hard-shelled, firmly closed.”

— Margaret Atwood, Cat’s Eye

Last month, while ambling up granite boulders in Yosemite National Park, I came across an emotional hiker. He stood near the edge of Nevada Falls, surveying the lush valley below, a smile ripening his sunburned cheeks. As I passed, he turned toward me. “Gorgeous!” he hollered, emphatically flapping his arm toward the cascade. “Doesn’t it just make you happy as a clam?”

I gave him an awkward thumbs-up and continued down the trail. Only later, while treading through a thicket of pines, would I question his statement: why the hell is a clam, of all creatures, the gold standard of happiness?

The closed-off, hardened mollusks are no more discernibly jocular than, say, a marmot or a woodpecker. Limbless and awkwardly shaped, they’re ordained to a life of salty tides; brainless, they wallow in utter nothingness. We shuck them, suckle them, and stew them alive in boiling cauldrons of doom. Despite these horrors, the Oxford Dictionary of Idioms cheerfully reminds us that he who is “happy as a clam” is “overwhelmingly joyous and content.”

Why?

![]()

Tracing the precise origin of an idiom is an unrewarding endeavor, often resulting in little more than speculation. “Happy as a clam” is no exception. Who found clams so jovial to begin with is anyone’s guess — though we do know that the phrase is a shortened version of a saying that was thrown around Northeastern harbors at the turn of the 17th century.

Most clams live and reproduce in shallow ocean waters. At low tide (when the ocean recedes furthest from the shore), clams are exposed and prone to humans and other predators snatching them up. Conversely, at high tide, they are “safe,” and therefore happy. Historians generally agree that sailors and shellfish gatherers began using the idiom “happy as a clam in the mud at high tide” (or “in high water”) by the mid-1600s, to describe feelings of euphoria.

The shortened, modern version of the idiom (“happy as a clam”) didn’t surface until centuries later, in 1833. On page 571 of Atkinson’s Casket, or Gems of Literature, Wit and Sentiment (a collection of philosophy, history, and terrible jokes), it was used to describe the unbridled merriment of a fiddle-playing slave:

Atkinson’s Casket, or Gems of Literature, Wit and Sentiment (Samuel Coate Atkinson, 1833)

A few months later, also in 1833, the phrase fond its way intoThe Harpe’s Head: A Legend of Kentucky, a frontier memoir. Here, is was used more appropriately, to relate the joy of a prosperous farmer:

The Harpe’s Head: A Legend of Kentucky (James Hall, 1833)

By the mid-1830s, the idiom had been recognized by writers and etymologists as a commonly enlisted descriptor for happiness and pleasure. For instance, an 1834 volume of Harvardiana, an old Harvard University journal, notes that “the phrase ‘happy as a clam,’ widely used, usually denotes a peculiar degree of satisfaction.” In 1838, New York literary magazine The Knickerbocker elaborated on exactly what it is that makes a clam so happy:

The Knickerbocker (March 1838)

Eventually, “happy as a clam” was even included in the Dictionary Of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words And Phrases Usually Regarded As Peculiar To The United States. “‘As happy as a clam,’” wrote the edition’s editor, John Russell Bartlett, “is a very common expression in those parts of the coast of New England where clams are found.” By 1848, the Southern Literary Messenger, a well-known Virginia periodical, suggested it was “familiar to everyone.”

![]()

While society was busy universally trumpeting the gaiety of clams, one man, poet John G. Saxe, had trouble understanding why. In his Sonnet to a Clam (1840), he itemized the struggles faced by the creature:

Inglorious friend! Most confident I am

Thy life is one of very little ease;

Albeit men mock thee with their similes

And prate of being “happy as a clam!”

What though thy shell protects thy fragile head

From the sharp bailiffs of a briny sea?

Thy valves are, sure, no safety-valves to thee,

While rakes are free to desecrate thy bed,

And bear thee off – as foemen take their spoil-

Far from thy friends and family to roam;

Forced, like a Hessian from thy native home,

To meet destruction in a foreign broil!

Though thou art tender yet thy humble bard

Declares, O Clam! Thy case is shocking hard!

Saxe had a point: what exactly should clams be so happy about? They’re stationed to a watery, stagnant existence, rife with jagged rocks and hungry sea creatures. Fish, shorebirds, seals, and even starfish (through some impressive maneuvering) all feast on the clam’s innards. Humans harvest no less than 10-17 million of them per year: At a moment’s notice, a clam can be whisked away from its loved ones and pulverized into a chowder, or made into a mermaid bra.

Of course, happiness is subjective. For thousands of years, philosophers, neurologists, and biologists have debated its origins and root causes. In one well-publicized theory, psychologist Martin Seligman surmises there are five determining factors that induce and influence happiness: pleasure, engagement in activity, relationships, accomplishments, and meaning. Essentially, clams sit around in mud eating small plants and fecal matter all day. They are also parthenogenetic, or self-reproducing, so they do not enjoy sexual relationships. According to Seligman’s factors of happiness, the prognosis is not good for clams.

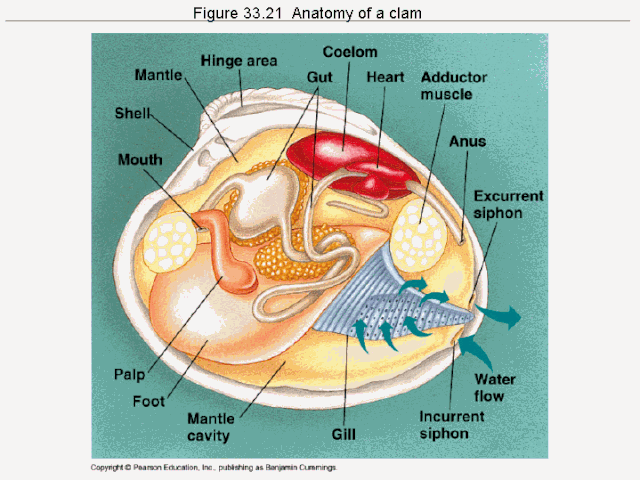

In fact, those who keep them as pets cite only two signs to tell if they’re happy: a mouth that is not “gaping” (a clam that opens too wide is under distress), and a mantle (or skin inside the shell) that receives frequent exposure. The clam is caught in an unpleasurable Catch-22: it can’t open its mouth too much or too little. What an existence.

The only conceivable argument one could make for a clam’s contentedness is its total and utter lack of awareness. As evolutionary psychologist Diana Fleischman notes, clams “have a very simple nervous system which is not aggregated in anything like a brain.” A sentientist, Fleischman believes that creatures besides humans have coherent thoughts and therefore are capable of suffering. Even she balks at the notion that clams have feelings (though this has yet to be scientifically confirmed):

“[Clams] do not have hardware or response consistent with the ability to feel pain. Because they have no brain, or central processing unit for stimuli…there is no place for sensations to be aggregated into responses or changes in adaptive decision making.”

One may say the clam finds happiness in its state of nothingness — but the creature’s ignorance of its own existence would then prevent it from realizing so. “I’d be very surprised,” adds Brown University psychiatrist Peter Kramer, “if mollusks have moods.”

In 1998 experimental biologist Peter Fong found clams so depressing that he fed them Prozac — apparently, in an effort to determine the creatures’ level of cognizance. Within a few hours, the clams were “[spewing] sperm and eggs all over the place.” Despite catalyzing an asexual orgy, Fong found no conclusive evidence that clams processed any awareness or emotion. The study did, however, have a disquieting outcome for clams: it provided clam farmers with a more convenient way to breed and harvest them for consumption. Even antidepressants knocked the poor clam on its proverbial ass.

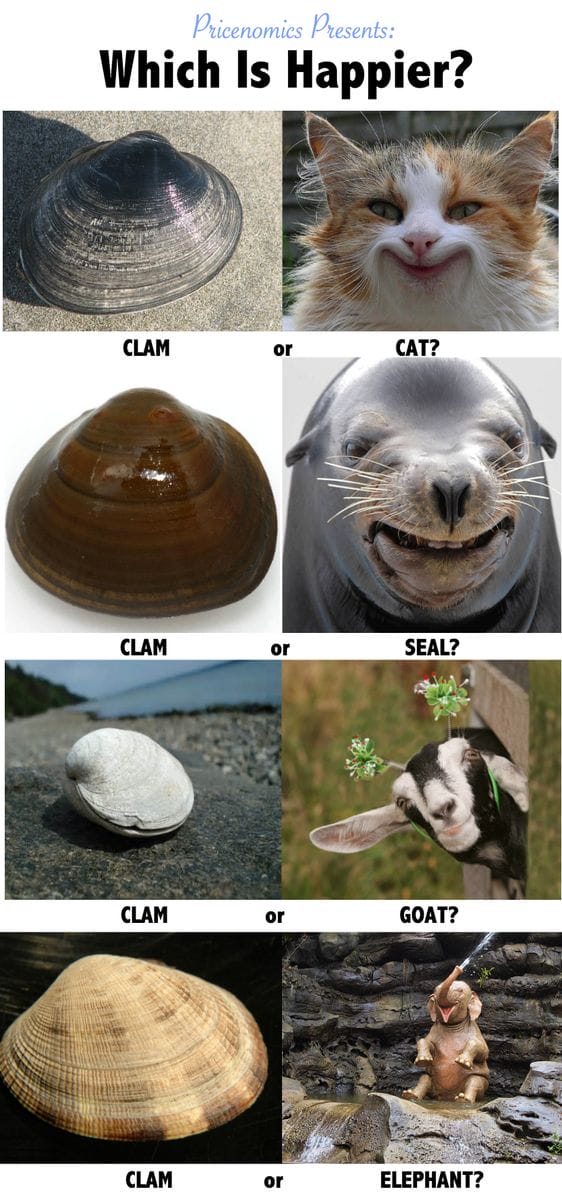

If you’re still convinced that the clam is the echelon of happiness, consider that millions of other creatures externally exude more convincing signs of joy. We offer you photographic evidence:

Still happy as a clam? For your sake, we sure hope not.

If you liked this blog post, you’ll be mildly amused by our book → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.