An orange slice

Robert was standing in the customs line at an airport in New Jersey when he realized he’d forgotten to eat the lunch he packed in France. Instead of declaring the apple and the orange he packed, he decided to smuggle them through, and then duck into a bathroom before the luggage scan and stuff his face in a stall.

He ate, swallowed, stepped out of the bathroom, and was greeted by a TSA officer and her barking dog. Robert was confused because as far as he knew he wasn’t carrying drugs.

“Oranges?” the woman asked.

“Oh, I had one,” Robert said. “But I ate it.”

The officer went through the trouble of searching his luggage anyways. Once she was satisfied that his pack was orangeless, she waved him on with an askance look.

“This wasn’t the first time,” Robert admitted to us. He said he didn’t declare his fruit because of an experience he had a few years ago, coming from Canada, when he declared an orange at customs and was detained for an hour. “There was a whole good-cop-bad-cop routine while the orange sat on the table.”

To most travelers, the customs line is a mostly-harmless inconvenience. But when you consider the resources state and federal governments put into regulating the import certain fruit and vegetables, even in small amounts, it can be a little perplexing. The officers, the dogs, the time. If you cross any state line, a human asks you if you’re carrying any fruits and vegetables. If you get caught holding the wrong banana you might miss your flight. Why all the fuss?

The fruits and vegetables travelers carry can contain diseases that can affect American crops. Citruses, like oranges, are particularly scrutinized because of the citrus canker disease, and because citruses are important domestic crops. But there’s a particular plant pest that gets special mention on the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s website:

One good example of problems imported fruits and vegetables can cause is the Mediterranean fruit fly outbreak during the 1980s. The outbreak cost the state of California and the federal government approximately $100 million to get rid of this pest. The cause of the outbreak was one traveler who brought home one contaminated piece of fruit.

The Lord of the Fruit Flies

Ceratitis capitata – the medfly

There was, in fact, a Mediterranean fruit fly “medfly” outbreak in the 1980s. And it was a huge deal to California agriculture, and consequently to California politics. But the idea that it was caused by “one traveler who brought home one contaminated piece of fruit” seems to be a total fabrication.

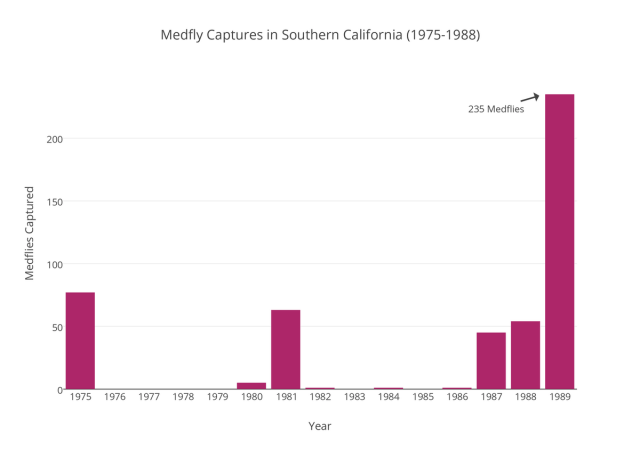

The female medfly lays her eggs in fruit — including California apples, apricots, avocados, bell peppers, cherries, dates, figs, grapes, grapefruit, kiwis, limes, mandarin oranges, nectarines, olives, oranges, peaches, pears, persimmons, plums, prunes and tomatoes. The eggs hatch into larvae, which then eat the fruit and turn it to unappetizing mush, metamorphose into flies which then go out into the world, mate, and lay eggs in more fruit. Early outbreaks in from 1975 onwards were thought to be independent — caused by several “reintroductions” of the pest by travelers in unregulated gifts of mailed fruit from Hawaii. We could find no record of a patient zero ever being identified.

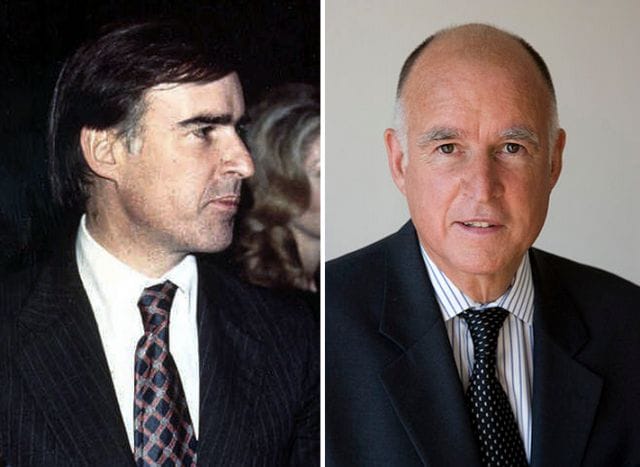

But then, in 1980, there was a bigger outbreak. While earlier infestations were treatable over-the-counter, the infestation of 1980-1981 was bigger. The US Department of Agriculture advised then-Governor Jerry Brown to authorize airborne spraying of large parts of residential California with pesticide (malathion). Brown, an environmentalist, only authorized ground-level spraying at first. A scientific advisor had prediced the population would die off in the winter. When it didn’t, the infestation spread. Embargoes were placed on California produce to prevent spread to other states — costing an estimated $73 million in crop damage. Then the federal government, fearing a widespread epidemic, threatened to put California produce under longtime quarantine if he didn’t spray.

A helicopter used for aerial application in the 1980s

An army of helicopters took to the sky, horrifying many adults and delighting some children — as this San Francisco Chronicle columnist recalls:

This was still 10 years before anyone started saying “wicked awesome” and 20 years before “hella awesome” entered schoolyard vocabularies. And yet somehow we knew that those words had to be invented. Because “awesome” alone just wasn’t enough to describe what you saw when you looked out your window an hour past bedtime, and five helicopters were swooping over your suburban Bay Area neighborhood in formation like something out of “Apocalypse Now.” […] Santa may not have been real, but in 1982, it seemed as if a Medfly pilot might land on your roof at any time, slide down the chimney and spray a bunch of that sticky white crap on your ficus plants.

Those “wicked awesome” helicopters were expensive. All told, eradication efforts ended up costing the state and federal government around $100 million — as the Customs website reported. Eradication was declared in 1982, but Brown lost on both fronts politically — he had failed to protect agriculture from significant crop loss, and he failed to protect suburban California from what protesters were calling “death from above”. Brown lost his 1982 bid for Senate in a defeat that many assumed would end the presidential-hopeful’s political career.

California’s oldest governor, and one of its youngest: Jerry Brown

When he was re-elected as Governor in 2010, one of his campaign promises was: “If I see a Medfly, I’m going to spray that sucker. I’m not waiting this time.”

Medflies resurged in the late 1980s, and have been a more or less annual battle since then. The government still sees smuggled fruit as a pathway for these outbreaks, but scientists now believe that even though medfly numbers are low, they’re now a well-established species in California’s ecology.

Brown’s promise might have merely been a metaphor for his more mature and active attitude towards politics: you won’t be seeing a malathion-spraying helicopter anytime soon.

The Breeders: Fruit Fly Terrorists

A 2008 protest in Marin: aerial spraying of pesticide is still politically unpopular, photo by Kevin Krejci

One of the reasons aerial spraying was so unpopular was that another option existed: the sterile insect technique. This involves the release of millions of lab-sterilized male medflies into the affcted region. Those male flies compete with virile males to mate with the females, suppressing population growth. The technique was used in conjunction with aerial spraying to combat even the earliest medfly outbreaks.

But it has its drawbacks: sometimes the laboratory fumbled the sterilization process and released non-sterile bugs by accident, and spraying was usually cheaper. Spraying continued as the primary containment technique through the 1980s until a huge medfly outbreak in 1989.

Data from an article in Ecology, 1996

In December of 1989 a group calling themselves “The Breeders” (not to be confused with Kim Deal’s side project) took responsibility for the surge in a letter to Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley sent to theLA Times and Fresno Bee. The Breeders said they’d been breeding the fly, and releasing pregnant females in areas immediately after they’d been sprayed since March. Their stated goal was to make the medfly ‘problem’ “unmanageable” and aerial spraying “politically and financially intolerable”:

“Our position is absolutely non-negotiable. Every time the copters go up to spray, we’ll go into virgin territory or old Medfly problem areas and release a minimum of several thousand blue-eyed Medflies. We are organized, patient and determined.”

Though the Breeders’ attack was never publicly verified as legitimate, and the group’s members were never identified, eradication experts admitted that the infestation pattern was unusual.

“There are some peculiar things happening,” government researcher Carol Calkins was quoted saying. Disproportionately more adult female flies had been found than males or larvae, and, “in a final riddle, many of the Medflies have been trapped just outside previous spray zones,” the LA Times reported, “forcing steady expansion of the area undergoing malathion treatments. Some experts said the pattern is as illogical as it is frustrating.”

Two months later the USDA took out a classified in the LA Times:

Breeders: If you’re for real send one of your little friends. We want to talk. Call John at USDA.

The ad included a phone number, which is much closer than the government gets to negotiating with most terrorists (the Breeders have been called agroterrorists — they held California produce hostage). If they ever got in touch with the letter writers, the correspondence was never publicized. But a month later, in March of 1990, the state announced plans for a “tactical shift” in the battle against the medfly. It would attempt to replace aerial spraying with the sterile insect technique. The state has relied “almost exclusively” on the release of sterilized insects since 1996.

The Counterterrorism to Agroterrorism

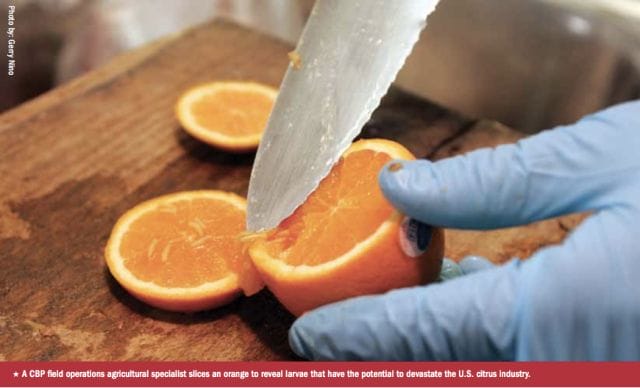

Photo and caption from US Customs and Border Protection Magazine Frontline, 2008

The Breeders’ letter made politicians aware of the fact that, whether or not the letter was a hoax, their economy was susceptible to deliberate insect attack. Also in 1990, California State Senator Ruben Ayala championed a bill elevating the crime of willfully and knowingly importing a medfly into California to felony status — “punishable by 16 months, two or three years in state prison and/or a fine up to $10,000”. Luggage scanners weren’t just looking for hapless tourists carrying ill-advised souveniers. They were looking for terrorists.

In 2003, in the heat of the War on Terror, this attitude towards agroterrorism was formalized at the federal level in a whole new way: The US Customs and Border Protection agency was formed to include the USDA and the Plant Protection and Quarantine program in it’s counterterrorism efforts. According to a 2008 issue of Frontline, CBP’s magazine:

Rather than looking only for accidentally introduced pests and diseases, [we now] also [have] to focus on intentionally introduced ones. […] Today, CBP sees its agriculture mission as seamlessly blending homeland defense with economic security.

Which is why the war on terror now extends to your orange: you might see it as a healthy snack, but Uncle Sam sees it as a potential weapon against the state.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list