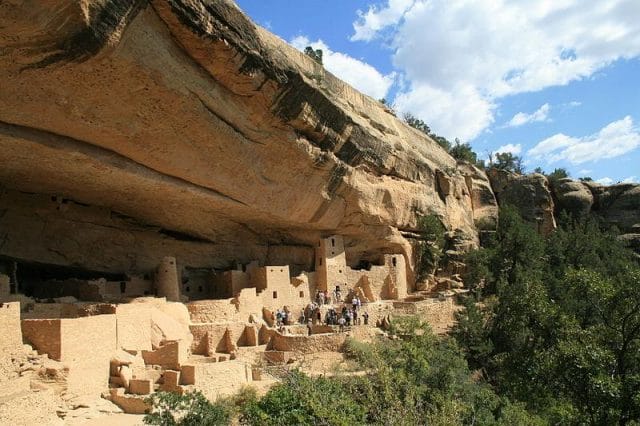

An image of the Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde by Andreas F. Borchert

In 1811, a young lawyer and journalist named Henry Brackenridge found the ruins of an ancient city near St. Louis.

At the time, St. Louis was a small, young city that served as the gateway to the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. Americans knew little about the new territory, and Brackenridge was struck by the size of the ruins. “If the city of Philadelphia and its environs were deserted,” he wrote, “there would not be more numerous traces of human existence.”

As archaeologist Timothy Pauketat has written, Brackenridge was standing on the site of what was once the Grand Plaza of Cahokia, a city inhabited in 1250 by some ten to twenty thousand Native Americans. Brackenridge believed he’d made a great discovery. He did not see ancient stone walls or worn foundations. Instead he marveled at the pattern of raised earth that resembled an urban grid, human bones, and mounds of soil formed into dozens of grassy pyramids up to 100 feet tall.

“I was struck with a degree of astonishment,” Brackenridge recalled, “not unlike that which is experienced in contemplating the Egyptian pyramids.”

But the world ignored Brackenridge’s discovery, and Americans have not treated what Dr. Pauketat calls “Ancient America’s great city on the Mississippi” with reverence. Four-lane roads and highways surround and bisect Cahokia, the sprawl of East St. Louis covers more of the ancient site, and many of the earthen pyramids have been scraped away to use as infill.

Cahokia has since been dignified with a state park and visitors center, but it’s not well known outside of Illinois and Missouri. It hardly attracts the number of visitors you’d expect for America’s version of the pyramids and the ruins of the country’s greatest, ancient city.

The same is true of impressive and important American Indian sites like the pueblos of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, and the pre-historic earthworks of Poverty Point in Louisiana.

Americans travel to Machu Picchu, Petra, Troy, and Angkor Wat. So why do so few visit America’s own ruins?

The New World: A Crowded Place

The concept of tourists flocking to American Indian archeological sites may seem strange if you learned in school—like this author did—that America was sparsely inhabited wilderness before Europeans arrived.

Through the 1950s, this was the consensus in academia. As journalist Charles C. Mann eloquently explains in 1491, a sweeping history of the Americas up to the arrival of Christopher Columbus, the most commonly cited estimate of North America’s population in 1491 was 1.15 million. That’s about the population of modern-day Rhode Island.

Yet early European colonists discovered that the areas they intended to settle were densely populated. When colonists like John Smith (of Pocahontas fame) established Jamestown, they became the neighbors of 14,000 Native Americans. As Mann writes, “The English were like the last people moving into a subdivision—they ended up with the least desirable property. Their chosen site was marshy, mosquito-ridden, and without fresh water.”

The steps down from Cahokia’s largest earthwork, Monks Mound, show how roadways bisect the site of Cahokia. Photo credit: Daniel X. O’Neil

Similarly, Mann notes that a French soldier exploring Cape Cod in 1605 decided that the area was too well settled to build a French base. And when Hernando de Soto pillaged his way through the American Southeast in 1539, his Spanish force regularly encountered thousands of Indian warriors and saw areas “very well peopled with large towns.”

The reason that Europeans could, decades later, settle unoccupied lands was that their predecessors had unleashed smallpox, bubonic plague, and the measles in the Americas. By living in close contact with domesticated animals like pigs and cows, residents of the Old World had incubated all sorts of diseases, which they then developed resistances to. The New World had few domesticated animals and no resistance to the dozens of diseases that appeared at once. When colonization began in earnest, European settlers found skeletons and abandoned villages.

This is part of the common understanding of American history. (Although in the 1600s and 1700s, many Europeans looked at the deaths as divine providence rather than tragedy.) But in the 1960s and 1970s, revisionist historians argued that the death toll—and therefore America’s pre-Columbian population—had been severely underestimated. Some believed that up to 18 million people lived in North America in 1491; a more conservative figure was seven million.

According to archaeologist Timothy Pauketat, seven million remains a common estimate. “The numbers many conservative archaeologists would give would be much lower, all the way down to one million,” he explains over email. “[But that’s] way too low.”

Once you add in revised estimates of the population of South America, the idea that Christopher Columbus “discovered” a “New World” appears even more absurd.

“Perhaps one human being in five was a native of the Americas,” James Wilson writes in The Earth Shall Weep, which uses the seven million estimate for the population of North America. “In 1492, the western hemisphere was larger, richer and more populous than Europe.”

America’s First Great City

The racist and ideologically convenient views held by European colonists of Native Americans as small, simple groups of people influenced interpretations of North American history.

When Americans did notice Cahokia’s ruins, most of them assumed that Indians could not have made them. They theorized that Vikings, Greeks, or Egyptians built the mounds; Thomas Jefferson advised Lewis and Clark to look for white, Welsh-speaking Indians who raised the pyramids. Even later archeologists struggled to imagine an Indian city.

That’s no longer the case. Dr. George Milner, who has excavated in Cahokia, believes that around 3,000 to 8,000 people lived in the city—a figure he calls “very respectable for a pre-industrial city… On a worldwide basis, that’s impressive.”

Dr. Timothy Pauketat, an archeologist who wrote a book about Cahokia, believes the city was home to over 10,000 people in 1250, with more Cahokians living on the surrounding farmland. If that’s the case, Cahokia was larger than London.

Cahokia is mysterious to historians because North America did not have writing systems, and Cahokia’s population disappeared suddenly and mysteriously in the late 1300s. By the time Europeans found the site, even Native Americans knew little about it.

What we do know is that a village was razed in 1050 to rebuild Cahokia on a grid, with a grand plaza and ceremonial structures built on two hundred huge, earthen pyramids. The population increased so rapidly—Dr. Pauketat writes that walking from the edge of Cahokia’s territory to the city center would have taken two days at its peak—that Cahokia must have drawn thousands of immigrants inspired by its religion, culture, or politics.

That culture included human sacrifices, which took place when Cahokia’s leaders were buried on its pyramids. The idea that cruel leadership may have driven away Cahokia’s immigrants is one of many theories for its demise.

Pueblos in Chaco Canyon. Photo credit: HJPD

We know what we know about Cahokia because Americans built a highway through it. The law that created the interstate highway system in the 1960s included funding to investigate archaeological sites that would be damaged, which meant scholars had funding and a mandate to study Cahokia.

Discovering that the mounds were actually the remains of the greatest city in North American history didn’t stop the construction of the highway or the expansion of the suburbs, which destroyed many of the pyramids and left roads crossing and surrounding Cahokia.

But what remained of Cahokia was already a state park, which UNESCO named a World Heritage Site in 1982, and the state built a visitors center dedicated to Cahokia’s history. Many St. Louis schoolchildren visit on field trips.

Cahokia receives around 250,000 visitors per year, and tourists from Germany, France, and the U.K. sign the guest book. That makes Cahokia a modest attraction—over one million tourists visit the Incan ruins of Machu Picchu (despite quotas that limit the number of daily visitors), and 1.5 million tourists visit the Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba, Spain, which was one of the world’s largest cities in Cahokia’s time.

Cahokia and other mound sites “have just never really gripped the imagination of the public,” explains archeologist George Milner. “People are more fascinated by photogenic places like Chaco Canyon.”

The ruins of pueblos built by ancestors of the Hopi and Pueblo people in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, are stunning. But they draw only 40,000 tourists annually. (Chaco Canyon is not easily accessible.) Like at Cahokia, the number of visitors has decreased in recent years.

The exception to this trend of disappointing turnout is Mesa Verde National Park, which is home to the Cliff Palace and draws 550,000 annual visitors.

Who Wants Tourists?

The tourism industry is not a bastion of free-market principles.

Instead governments are active participants who compete for tourists’ attention and wallets. Governments do market research and marketing. Governments build highways to remote destinations. Governments provide security and regulate tour operators.

You might suspect that few people visit Cahokia because earthen mounds are not that inspiring (although the Egyptian pyramids are really just piles of rocks). Or because the large pueblos and cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon are remote (although tourists flock to isolated sites like Machu Picchu and the Valley of Kings).

But imagine if the Southeastern United States were today a country inhabited and led by Mississippians whose ancestors had built the earthworks that still dot the region. The Lonely Planet guide to the country of Mississippi would list dozens of operators that led tours of the ancient earthworks, and Cahokia’s ruins would be the can’t-miss attraction.

“The main pyramid offers views of both the St. Louis skyline and the plaza where around 10,000 Cahokians once lived,” the guidebook would read, “and is the most popular selfie spot in Mississippi.”

But in reality, this is how a National Geographic writer described the same view when he visited Cahokia in 2010:

I just can’t get past the four-lane gash that cuts through this historic site. Instead of imagining the thousands of people who once teemed on the grand plaza here, I keep returning to the fact that Cahokia Mounds in Illinois is one of only eight cultural World Heritage sites in the United States, and it’s got a billboard for Joe’s Carpet King smack in the middle of it.

The Greek government loves to invest in the Parthenon, and Greeks love to visit it. But Indian sites are more likely to remind Americans of the Trail of Tears and treaty violations than appeal to their nationalism.

“Cahokia doesn’t mesh with the narrative of what the U.S. was like,” explains Dr. Adrienne Keene, a Native scholar and activist. “We are taught that nothing was here, so Native people deserved to have their land taken away. There would be less excitement about making Cahokia a national monument: that’s how white supremacy and colonialism work.”

The lack of enthusiasm for promoting Cahokia is evident on its website, which advertises a crowdfunding campaign for its marketing efforts:

Due to the economic conditions of the State of Illinois and the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, no funding is available for public outreach, community events, and marketing. All of these activities are funded solely by the support group the Cahokia Mounds Museum Society.

But even if Americans did invest in Native archeological sites and wanted to visit them, many American Indians might still feel wary about welcoming them.

Camille Ferguson is the Executive Director of The American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association (AIANTA). When we talk over the phone, she explains that many sites, unlike Cahokia or Chaco Canyon, are owned by tribes. And those tribes often lack the funding to build the infrastructure and provide the security a tourism attraction would need.

“A lot of the native archeological sites that have been found have been taken advantage of,” Ferguson says. “Tribes are trying to do repatriation—to get [stolen artifacts] back.”

This state tourism video shows some of the earthworks built between 1650 and 700 BC in Poverty Point, Louisiana.

Theft is not the only concern; so is respect.

Dr. Keene, for example, has several friends who portrayed American Indians at Plimoth Plantation, a “living museum” in Massachusetts that re-creates rural life in 17th century New England. “Visitors thought they weren’t native because they didn’t look like a Hollywood Indian,” says Keene. “Or people asked them about the Washington football team. The public still leaves with the impression that natives were savage or uncivilized. These experiences are hard on native people.”

There are no residents of Stonehenge or the pyramids. But the relatively young ruins of North America are still homelands to many native peoples.

“We call them sacred sites—not necessarily archeological sites,” Camille Ferguson explains. “The sacred sites are where the grave sites are. It’s something that hasn’t really been looked at as an attraction as much as something to be protected. I like to see ruins, but some of those cultures are very much alive.”

This sentiment pervades The Inconvenient Indian, a book by Thomas King. In the same way that Ta-Nehisi Coates explains in Between the World and Me what it feels like to be a black man in America, King explains what it feels like to be an Indian in North America. And to be an Indian, King writes, is to feel like an inconvenience. Because Indians were “supposed to” die out.

“The demise of Indians was seen as a tenet of natural law,” King writes. “‘The sun of their days is fast sinking in the western sky’… Problem was, Live Indians didn’t die out… [so] as the nineteenth rolled into the twentieth century, Live Indians were forgotten, safely stored away on reservations.” Americans are comfortable with seeing “Dead Indians” in traditional garb on packages of butter or in Western films, but a Live Indian in a suit seems “inauthentic.”

This is why Camille Ferguson, speaking on behalf of many American tribes, is happier talking about new cultural centers than ancient ruins, which cement the idea that Indians have died out.

“Tribes want tourism to be a way of perpetuating their culture,” she says, “not just putting it in a museum.”

***

Sites like Cahokia and Chaco Canyon are underappreciated, but North America does have fewer ancient ruins than many parts of the world.

This is because the largest cities in the Americas were in Mexico and South America—the home of the Incas, Mayans, and the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, which, in 1519, Charles Mann writes, caused Spanish conquistadors to “gawp like hayseeds at the wide streets, ornately carved buildings, and markets bright with goods from hundreds of miles away. They had never before seen a city with botanical gardens, for the excellent reason that none existed in Europe.”

But in North America, Cahokia was the lone great city. Why?

According to Dr. George Milner, “you can find as many opinions [on that question] as archeologists.” The theory presented by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, however, is that North America never developed the intensive agriculture to support permanent farms and dense cities.

But judging the natives of North America by the number of large cities, ancient, stone towers, and permanent farms is making the same mistake as the early Europeans.

Photo credit: James Q. Jacobs

In 1491, Charles Mann writes that “Europeans tended to manage land by breaking it into fragments for farmers and herders. Indians often worked on such a grand scale that the scope of their ambition can be hard to grasp.”

Indians primary tool for reshaping their environment was fire. During the Civil War, American troops in Virginia’s woods could barely see each other through the dense underbrush. But when Europeans first arrived, they marveled that they could ride a horse straight through a forest. The difference was that Indians had once cleared out the underbrush with fires so large that the earliest colonists watched the burns like they were fireworks.

Not every part of North America was transformed in this way, but in many areas, Mann writes, “Indians retooled whole ecosystems to grow bumper crops of elk, deer, and bison…. Millennia of exuberant burning shaped the plains into vast buffalo farms.”

Much of what European explorers saw as rich, untamed wilderness was actually what Mann calls “the world’s largest garden.”

“It was an altered landscape,” Dr. George Milner explains. “But Europeans didn’t recognize it as such.”

This is the irony of Americans’ indifference to the country’s archeological sites. By 1492, American Indians had created a giant park whose beauty and riches inspired thousands and thousands of Europeans to cross a continent.

They just failed to realize what they were seeing. And now it’s gone.

Our next article investigates the business of storing nuclear waste that will be lethal for the next 10,000 years. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This article was updated on September 11, 2016. The original article said native actors at Sturbridge Village had faced disrespectful questions. But Dr. Keene actually referred to actors at Plimoth Plantation. We regret the error.

![]()

Announcement: The Priceonomics Content Marketing Conference is on November 1 in San Francisco. Get your early bird ticket now.