Neal Stephenson knows a thing or two about science fiction. The author of thick, best-selling novels that cross genres but slant toward sci-fi, Stephenson also writes about technology and has worked part time on a private space company.

He is also tired of dystopian science fiction movies and video games. “A few weeks ago I think I actually groaned out loud when I was watching Oblivion and saw the wrecked Statue of Liberty sticking out of the ground,” he tells Morgan Warstler in an interview.

A proponent of the thesis that we have “lost our faith in technology to bring progress” and “lost our ability to get important things done” on an Apollo mission scale, Stephenson sees the ubiquity of dystopian visions as a cultural expression. Whereas it was once “refreshing, and extremely hip, to see depictions of futures that were not as clean and simple as Star Trek,” we now experience “a strange state of affairs in which people are eager to vote with their dollars, pounds and Euros for the latest tech [like iPhones], but they flock to movies depicting a relentlessly depressing view of the future, and resist any tech deployed on a large scale, in a centralized way.”

Just after expressing his literary take on the preponderance of films like District 9, Oblivion, and Children of Men, however, Neal Stephenson also offers an extremely Priceonomics explanation for why sci-fi movies keep depicting the future as a rundown San Francisco or Manhattan rather than a dizzying alien world: it’s cheaper. He tells Warstler:

“I hope I won’t come off as unduly cynical if I say that such people (or, barring that, their paymasters) are looking for the biggest possible bang for the buck. And it is much easier and cheaper to take the existing visual environment and degrade it than it is to create a new vision of the future from whole cloth. That’s why New York keeps getting destroyed in movies: it’s relatively [easier] to take an iconic structure like the Empire State Building or the Statue of Liberty and knock it over than it is to design a future environment from scratch.”

The problem with a sci-fi blockbuster that brings to life a singular vision of a new world (à la Avatar) is that it’s expensive and not reproducible. In contrast, “putting dirt on the Empire State Building” is a cheap and safe decision (it’s worked before) that appeals to executives as a way “to create a compelling visual environment, for minimal budget, of a future world.”

We lack a direct line to Jerry Bruckheimer’s office, and Hollywood finances are notoriously opaque and deceptive, so entertainment insiders should chirp up about the veracity of Stephenson’s theory.

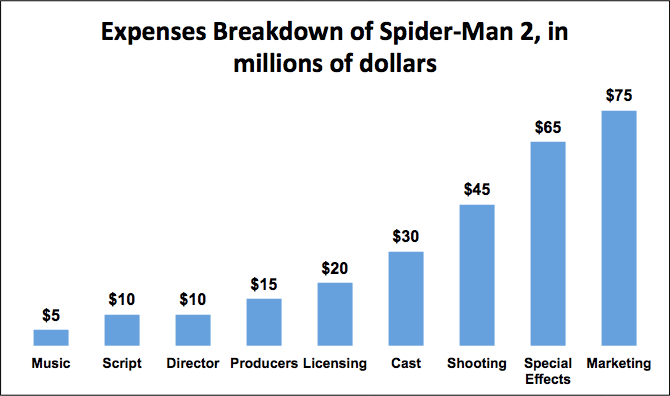

Still, we can see why the cost of creating the setting for a blockbuster could determine what types of stories get told. The below chart shows the breakdown of expenses for the making of Spider-Man 2, as reported in The Guardian. The finances are, apparently, garnered from industry gossip. Yet they provide a rough sense of where the money goes.

Data from The Guardian. Expenses are all estimates based on industry gossip.

As we can see, the cost of writing the story (labelled “script” in the chart) is $10 million, which is a fraction of the $65 million cost of special effects. For this reason, Stephenson argues, the story is “entirely secondary and [is] generally pasted on as an afterthought.” Instead the much larger costs of the special effects and shooting the film drive decisions about which stories Hollywood makes.

From an outsider’s perspective, we can offer a few retorts to Stephenson’s idea.

One is that Hollywood producers are actually not motivated to lower production costs, preferring the arms race of making bigger and bigger blockbusters. As argued in The Guardian:

Although studio executives protest that they are forever working at reducing production costs, there is a vested interest in big-budget, effects-heavy blockbusters. By pushing the cost through the roof, they keep a stranglehold on the capability to create grand scale projects and the access to the considerable financial upsides of the hits.

But a stronger response is that the cost of creating a sci-fi universe is as equally unimportant as writing compared to the strongest economic imperative of Hollywood: will it produce lucrative opportunities for merchandise, sequels, and TV spin-offs?

According to Edward Jay Epstein, author of The Hollywood Economist, Hollywood makes roughly 10% of its profits from the domestic box office, another 10% from foreign box office, and 80% from these other monetization options. The result, according to an entertainment journalist, is that “However strong the characters and storyline, none of the new breed of blockbusters gets the go-ahead unless it can justify itself in terms of its TV spin-offs, sequels, merchandising opportunities and DVD tie-in.”

So story is still an afterthought, but this suggests that the ability of a familiar franchise to provide sequels and sell merchandise, even if it requires an expensive and novel set, appeals most of all to executives. And indeed, films like Avatar and Inception are rarities in the list of highest grossing sci-fi movies, which features franchises like Star Wars, the Hunger Games, and Transformers.

Great science fiction can shape our expectations of the future, probe the uncertain implications of technological progress, and ask moral questions through analogy. The economics of Hollywood, however, drive executives to present audiences with the visions of the future with which they are already most familiar.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list. Hat tip to Tyler Cowen and Marginal Revolution.