In this author’s utopian future, all television is available to be streamed on demand. Turf battles between media companies have given way to universal access: Last minute scrambles to find someone with an HBO Go password minutes before the Game of Thrones premier are no more. Advertisements are rare or unique to the Super Bowl, leaving our brains free to remember things other than jingles for Applebees and car insurance.

Like most utopias, this one may be flawed. But not for the reason you expect. The problem may be that the lack of television ads renders TV less enjoyable.

The reasoning behind this claim comes from positive psychology – which can colloquially be summed up as the psychology of happiness and fulfillment – and its major tenet that people’s level of happiness adapts to changes in circumstance. Buying a sports car or moving to a less posh neighborhood may make us giddy or gloomy, but only for a brief period. Eventually we adapt, incorporating the new circumstances into our normal state of affairs and ceasing to see an effect on our happiness.

The inevitability of adaption varies in strength but seems fairly inevitable. We adapt much more to the benefits of a larger television than to a new relationship, for example, yet men and women report a higher level of happiness after marrying. After one to two years of marital bliss, they return to normal, premarital levels.

This could equally apply to our enjoyment of television. Imagine settling on the couch to watch Modern Family, relishing the freedom from work and family. Just as the first burst of dopamine is about to wear off, Modern Family cuts to a commercial. You sigh, study the marks on the ceiling, and complain that Budweiser needs to fill its ads with attractive women to distract from its terrible taste. But then Modern Family returns and with it your enjoyment of its lovably repetitive storylines.

It’s not necessarily intuitive that commercials are worth the pain – even with these ideas from positive psychology in mind. But a 2009 study suggests that ads can improve the enjoyment of television.

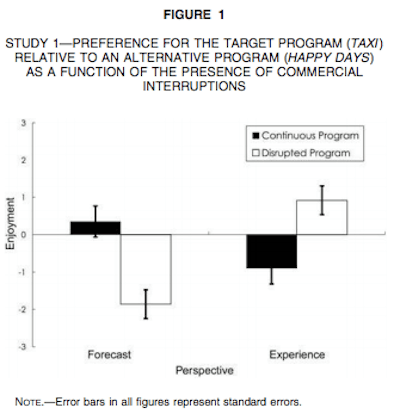

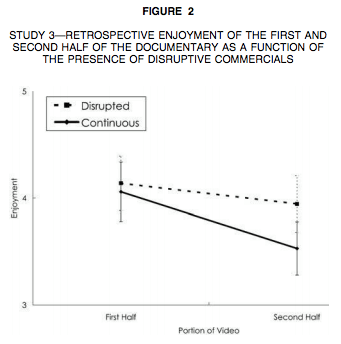

To test the hypothesis, researchers first had undergraduate students watch a sitcom (Taxi) with or without commercial interruption. The students then indicated their enjoyment by reporting how much they would pay for a DVD of the show, comparing it to another show (Happy Days), or reporting their enjoyment or how funny they found the episode. The researchers then tried to control for other factors in three subsequent variations of the study: They had participants watch a nature documentary instead of a sitcom, interrupted the show with a clip similar to the program instead of an ad, and had the control group watch ads before and after the television show.

In each case, participants reported more enjoyment of the episode disrupted by commercials, consistent with the hypothesis that advertisements prevent people from adapting to (in effect, getting bored by) TV shows.

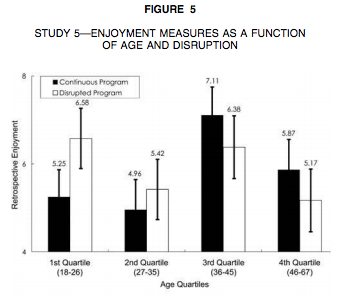

A fifth expirement, however, suggests that with age comes the wisdom to enjoy hours of television without the breath of vapid air supplied by advertisments. The researchers found that viewers age 36 and over prefered episodes without commercial interruption. Full results and methodology are available here.

A corollary of these findings is that movies are more enjoyable in theaters overseas, where intermissions are common, than in American theaters, where they are not.

This also suggests a happy ending to our story – and it’s not just that media companies like Time Warner Cable are adept at clinging to their business model. Commercials improve our enjoyment of TV because of the respite they provide – the content devised by wannabe Don Drapers is irrelevant. In the utopia ad-free future, you can simply take your own intermissions in lieu of commercials by making a snack or walking the dog.

Even better, television may be changing to be less reliant on ads to keep us engaged and happy. In a final experiment, the researchers found no adaptation or increased enjoyment from interruptions when the undergrads watched a novel clip. (They used clips from Bollywood movies, assuming that American undergrads were unfamiliar with the long song and dance sequences of Indian films.)

While lacking data to back them up, the study’s authors speculate that “very fast-paced and complex shows, such as ’24,’ probably do not benefit from commercial interruptions” as viewers adapt less to their plot twists and linear story lines than they do to circular sitcoms or reality shows. They note:

Popular television may, in fact, have evolved to maximize experience by minimizing adaptation. For example, it has been argued that television programming has grown more complex, with precisely the types of jarring editing and elaborate writing that keep people from adapting to a program.

Television critics have argued that we have entered a new golden age of television as companies like HBO and AMC invest in sophisticated shows like Game of Thrones and Mad Men. The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson credits the business model of cable television, which prioritizes critically acclaimed hits over shows produced for a mass audience. If the researchers are correct that writers and directors are responding to how we adapt to television by making it more complex, then our wishful move toward ad-free streaming could kick that evolutionary imperative toward better writing into overdrive.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.