Cunningham’s Law: “The best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question, it’s to post the wrong answer.”

The Internet has been a boon and a curse for journalists. It threatens to destroy the entire industry, of course, by stealing away its advertising dollars. It has also led to new and creative digital media ventures while making it infinitely easier to research (and rehash) stories. One tool, in particular, rivals the search engine in its utility for journalists: the ability to quickly and effortlessly solicit crowdsourced research and dozens of expert opinions on any topic.

Writing 1,200 words about San Francisco’s housing market? How would you like comments from Mayor Ed Lee, tech executives, and NGOs that work on affordable housing? And how about an army of people offering links to relevant reports, fact-checking eviction numbers, and making the case for each side of the argument?

Writing about a protest in Egypt? How would you like foreign policy experts to critique your take? Or protesters to come out of the woodwork to corroborate or refute the account you received from interviews?

This is a journalist’s dream, and in the age of the Internet, it actually happens. There’s just one problem: It happens after journalists publish a story, as people share and react to the article. In other words, when the information is mostly useless to the author.

Journalists have a strange job. There are beat reporters with area expertise and a rolodex of contacts who keep them regularly informed about Wall Street, the White House, or whichever beat they cover day in and day out. But for the rest of us (if lowly Priceonomics writers may lay some claim to the title of “journalist”), the job entails writing authoritative takes on topics we knew almost nothing about days or (at best) weeks earlier. It’s a bit like Mark Wahlberg playing a cop after going on a few ride-alongs, or Kevin Spacey hanging out on Capitol Hill to prepare for House of Cards. Just less handsome.

Journalists do always have the recourse of quoting experts or voices on each side of a story when the truth is elusive. Still, not to complain too much, when need to become an expert in a few days, deadlines can loom before you even know who you should talk to. This author was several pages into a story about cyborgs and a day away from his deadline when he learned about a man with a piece of hardware called “the eyeborg” fused on his skull.

A guy who charges the chip in his skull with a USB cable. Who knew? Millions of people with an Internet connection, actually, but they won’t tell you until you publish a story about cyborgs that doesn’t include the eyeborg guy. Then they’ll do so with a vengeance.

This is the frustrating truth of Cunningham’s Law: the idea that “the best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question, it’s to post the wrong answer.”

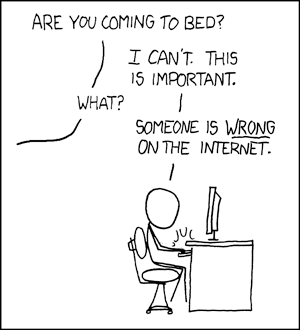

It’s possible to take advantage of the Internet to do some of this crowdsourcing for a story. For its investigation of unpaid internships, for example, ProPublica solicited people’s stories and opinions about the topic through Twitter. But as the law (and this comic from xkcd) suggests, posing the question is not nearly as powerful a call to action. People may respond to journalists’ questions on Twitter and Facebook, and many experts and individuals show a surprising amount of patience with journalists’ questions.

“Duty Calls” by xkcd

But nothing motivates anyone and everyone on the Internet to action like seeing someone write something (they at least regard as) wrong. Helping a journalist with a story is nice; unleashing a can of whoop ass on a journalist who got the story wrong, or someone in the comments section, is a holy crusade. The only thing that matters.

When Priceonomics investigated some baffling research on perceptions of wine, a few people in the industry told us what they thought. But wine connoisseurs did not exactly get in line to answer a nosy economics blog’s questions. When we published the post, however, under the admittedly provocative title of “Is Wine Bullshit?”, we had no trouble getting feedback. (For the record, we came out on the “no” side, but the answer is more complex than you’d think.) With a viral article casting some doubt on their profession, suddenly master sommeliers — whose opinion we very much would have liked to include in the article and based our conclusions on — weighed in.

This being the Internet, the feedback was usually in insult form, full of vitriol, and contained the occasional sadistic threat. But we did learn valuable information about how some people in the wine industry regard tastings as more of marketing gimmicks than valid competitions, problems with the studies we cited, and so on. Of course, it was too late to use that information in the article. At best we could note it in the comments or at the end of the article.

In a more typical example, when we wrote about the outdated journal system for publishing scientific research, reactions to our article unearthed all sorts of interesting debate about the problems with current open-access journals that we had not yet come across. It’s gratifying when an article prompts genuine discussion. (Note to idealistic writers: this is rare.) But most people will only see the article.

So, what now?

In digital media, there’s no particular reason that articles should always need to be final. (Except the journalists’ limited time, and the fact that the vast majority of traffic to an article comes in the first few days after it’s published, even if it remains relevant for years.) Ezra Klein’s new media venture at Vox plans to constantly update “primers” on topics in just this way.

Or perhaps some enterprising journalist could create the infrastructure to allow people to weigh in before publication. But it likely wouldn’t be as useful. The nuggets of good feedback come from a popular article making its way to people with the relevant experience, anecdotes, or willingness to play detective on that specific story, wherever they are. Responding to journalists’ first tentative drafts isn’t fun. The fun is in joyfully tearing the journalist a new one over his or her finished product.

Maybe journalists need to follow Cunningham’s law and publish something patently wrong (but in provocative, link-bait form) under a pseudonym somewhere, and then use the flood of critical feedback to write the real thing. But where would we ever find someone whose business model is to publish poor quality, incendiary, incorrect writing?

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.